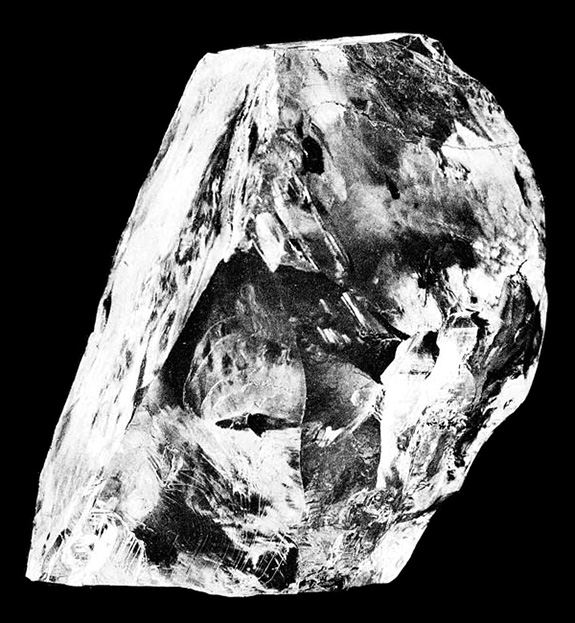

With the passing of Queen Elizabeth II, much has been written about the British Crown Jewels and the massive diamonds at the center of the Sovereign’s Sceptre and the Imperial State Crown.

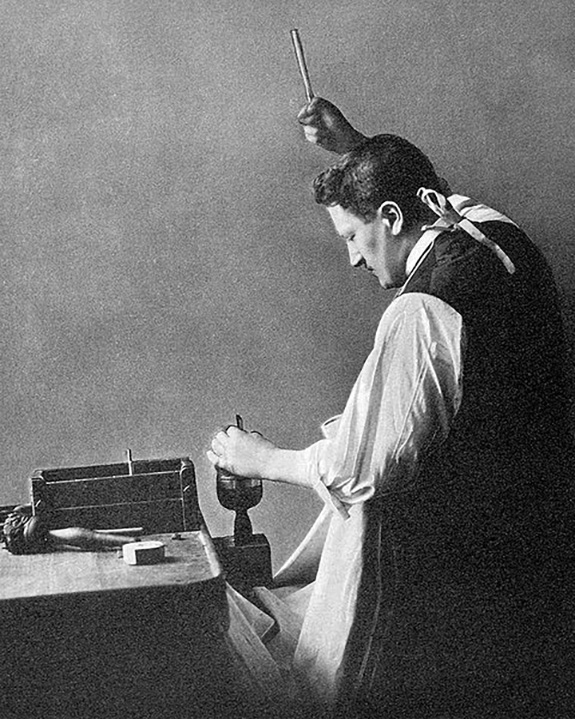

Both diamonds were expertly cut from the 3,106-carat Cullinan — the world’s largest rough diamond — by Joseph Asscher of the Amsterdam-based Asscher Company. What most people don't know is that the expert cutter was paid for his work in "chippings" and that some of those fragments still live more than 100 years later in the bridal sets of Asscher's descendants.

King Edward VII, Queen Elizabeth's great-grandfather, chose the Asschers for the high-profile job because they had successfully cut the previously largest known diamond, the 995.2-carat Excelsior, five years earlier.

After an extensive period of studying the stone, which had been discovered in 1905 at the Premier Mine No. 2 near Pretoria, South Africa, Asscher started the cutting process by creating an incision in the diamond of approximately 6.5mm deep.

It has been reported that Asscher broke his tool when he initially struck the stone. A week later, after developing stronger tools, Asscher successfully cleaved the the Cullinan into two principal parts, weighing 1,977 carats and 1,040 carats.

Asscher performed the failed first attempt in front of an audience of notables, but his second successful attempt was accomplished with nobody in the room, except for a Notary Public. Legend has it that Asscher struck the diamond so hard on the second try that he fainted after it split.

Over the following months, these diamonds were further polished and cut to create nine principal stones, 96 smaller diamonds and a quantity of polished “ends.”

The largest of the Cullinan gems, the Great Star of Africa (Cullinan I), weighed 530.4 carats and was set atop the Sovereign’s Sceptre. The 317-carat Second Great Star of Africa (Cullinan II) was set in the Imperial State Crown.

It took Asscher and his team more than two years to complete their work. Asscher agreed to be paid in “chippings,” the diamond remnants that split off the main stones during the cleaving and cutting processes.

Now, more than a century later and in light of Queen Elizabeth II's passing, members of the Asscher family have come forward with stories about how these "chippings" from the Cullinan diamond are part of their own family heirlooms.

Israeli journalist Shakked Auerbach, who is a descendant of the Asscher family, recounted in a blog item published on the Israeli National Library website that diamonds belonging to her family were originally part of the 3,106-carat Cullinan.

She confirmed that Joseph Asscher, her great-great-great-grandfather, was paid in "chips." His fine work was also acknowledged in 1909 when he received a knighthood from the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

“The Asschers decided that the diamonds would be passed from generation to generation when men would give them on an engagement ring to women that would join the family,” Auerbach wrote.

Auerbach also shared the story of how the fist-sized Cullinan was secretly transported from England to the The Netherlands for cutting.

She wrote that the stone was loaded into the belly of a British battleship in a protective box. But it turned out that this London-to-Amsterdam transport was just a ruse.

It actually traveled in the pocket of Avraham Asher, who sailed from London to Amsterdam on an ordinary ship without carrying luggage. The only thing he brought on the voyage was the "large coat to protect him from the cold and disguise his precious cargo," she wrote.

Auerbach also noted how some of the Cullinan "chips" were hidden from the Nazis by Holocaust survivors, including her grandmother. Those chips have been since passed down through generations of the Asscher family.

"This is how my family was connected to the royal family," she wrote. "And who knows how the journey of the diamond will continue from here?"

Credits: Joseph Asscher photo by Unknown authorUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Cullinan rough stone by Unknown authorUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

No comments:

Post a Comment